Life & Work

Pete Seeger (1919-2014) had an enormous impact on the world today. Hundreds of leading musicians from Bob Dylan to Bruce Springsteen to Dar Williams trace their musical roots to Seeger's work. He worked tirelessly for over 75 years for a wide variety of social causes from better working conditions for working people to the Civil Rights Movement and from peace to protecting the earth.

Family Roots. Seeger was born in 1919 to Charles and Constance Seeger. Charles was a noted musicologist and Constance was violist. His family was from his earliest years involved in the thick of New York City musical and radical circles. His father later divorced and remarried to Ruth Crawford Seeger. In 1948 Ruth published a pioneering collection entitled American Folk Songs for Children. Pete married Toshi-Aline Ohta in 1943. Toshi worked with Pete on a wide variety of shared causes since that time.

Pete's older brother John served for many years as a school principal and summer camp director. His half siblings Peggy and Mike are renowned musicians in their own right. Peggy is the widow of Scottish folksinger Ewan MacColl and has written many songs. Mike (1933-2009) was a member of the bluegrass band, New Lost City Ramblers. Toshi and Pete had 3 children Danny, Mika and Tinya. Pete has often performed in recent years with his grandson Tao Rodriguez Seeger. Something about singing with Tao brings out the best in Pete's voice, worn down by too many years of trying to lead countless crowds in song, often without a mike. Tao was a member of the band The Mammals. (You can hear Pete and Tao singing together on Pete's CDs Seeds and At 89.)

Early performing years. At the age of 19, Pete dropped out of Harvard (which still welcomes him back as an alumnus...) to bum around the country with a little known at the time songwriter named Woody Guthrie. Woody and Pete performed at labor rallies, visited with other singers, and just soaked up a lot of the life of ordinary working people. Pete entered the army in 1942 and spent a lot of the war (once they army stopped investigating him) performing to his fellow soldiers.

After the war, Pete formed a group with Woody Guthrie called the Almanac Singers. They performed at political and union events during the post-war years. In 1949 he formed a new singing group with Lee Hays, Fred Hellerman and Ronnie Gilbert called The Weavers. The Weavers had such an infectious sound that their single "Goodnight Irene" went to the top of the charts. But these were the years of Joe McCarty and the anti-Communist "witch hunts". When the music industry discovered the group's left-wing connections, the group was blacklisted. Neither the Weavers nor Pete Seeger were allowed to perform at major concert halls or receive radio airplay through regular commercial stations for the next decade. Pete himself was called to testify before the House Un-american Activities Committee. Pete and Toshi say that for several years they expected Pete to be sent to prison for contempt of Congress for refusing to testify against his musician friends.

Political contributions. Pete was actively involved in the Civil Rights movement of the 1960's and played a role in the evolution of the song "We Shall Overcome" into the freedom anthem sung around the world. He was censored during a live broadcast on the Smothers Brothers Show on network TV in the mid-sixties for performing "Waist Deep in the Big Muddy", a satirical antiwar song about Lyndon Johnson. He performed at countless peace rallies through out the Vietnam War.

After the Vietnam War ended, Pete became deeply involved in the environmental movement. He and Toshi helped those concerned about water quality on the Hudson acquire a sloop called The Clearwater. Pete sailed up and down the Hudson River with young environmental activists and schoolchildren organizing and educating about the need to stop fouling our own waters. Pete & Toshi founded an annual festival to raise money for environmental causes called the Hudson Clearwater Revival, held each June a little north of New York City. Toshi served as the festival's musical coordinator for decades.

Pete's songwriting. Pete wrote or co-wrote scores of well-known songs including "Where Have All the Flowers Gone", "If I Had a Hammer", "Turn, Turn, Turn", and "Bells of Rhymney". He also adapted and introduced audiences widely to many other songs like "Wimoweh", "How Can I Keep from Singing", "Guantanamera" and (as already mentioned) "We Shall Overcome".

Pete's songs are so widely sung, that people are often unaware where the songs came from. Years ago the Kingston Trio recorded "Where Have All the Flowers Gone" and assumed it was a traditional song. When Pete mentioned to the group that he had actually composed the song, they were mortified!

Unfortunately, because Pete often minimized his own role in adapting or spreading many songs, he sometimes inadvertently undermined the musical contributions of some of his own musical friends. when "How Can I Keep from Singing" was published in Sing Out! Magazine in the 1950's, Pete failed to credit Doris Plenn, a family friend, for a new verse she had written to this old gospel song. When Enya recorded the song many years later and it was a big hit, his publisher lost the suit to claim royalties for Doris. The same result happened when a popular musician wrote English lyrics to the song "Wimoweh", a song he had learned from South African singers but had popularized widely through his own signing. When the song made a fortune when it was included in the Disney movie "The Lion King" many years later, the big industry lawyers won out again and Pete's managers' lawyers were unable to win royalties for the South African musicians who originated the song.

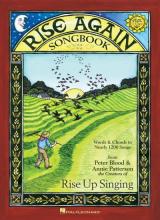

After Pete's long-term manager Harold Leventhal lost the court case to recover royalties for "Wimoweh" from Disney, Harold asked Pete to write a book about his songwriting that included all the songs he had written, co-written, or become deeply involved in in other ways. Harold's main goal was to prevent these songs from slipping into public domain. After some initial reluctance, Pete embraced the project. Because of his appreciation of the work Peter had done on Rise Up Singing, Pete asked Peter to serve as editor of the new book. The book, Where Have All the Flowers Go, eventually evolved into more of an autobiography than a songbook. It is filled with pictures from the Seeger family scrapbook and of stories of what was happening in Pete's life as he wrote each of the songs in the book. It is also filled with his ideas and belefs about the creative process, multiculturalism, social change, and a host of other topics dear to his heart.

Group singing. Part of Pete's genius has been as a songleader. He has been able to teach huge audiences around the world to learn and throw their voices into songs with him. He has been a tireless advocate of the idea that music and song and aspirations belong to all, not just to a few. As such he was an enthusiastic supporter of Winds of the People, the singalong predecessor to Rise Up Singing.

When we told Pete in the early 1980's that we wanted to make a new improved singalong collection, he helped persuade the board of Sing Out to take the project on. His publisher, Harold Leventhal, played a key role in obtaining copyright permissions from major music publishers like Hal Leonard and Warner Brothers Music. Pete helped us choose songs and wrote Rise Up Singing's powerful introduction. (You can hear Pete movingly reading this intro near the end of Jim Brown's documentary film The Power of Song.)

Multiculturalism. He also worked ceaselessly to celebrate cultural diversity. He believed the world's survival depending on peoples' capacity learn from each other. His concerts were always filled with songs and stories from around the world. His own songs often have drawn on a wide variety of sources woven artfully into new creations - putting new lyrics to an old melody here, putting a poem to music there, or adapting a song to make it more powerful and singable so it gets picked up by millions of people around the world.

It has been tough to identify Pete's contributions because he always shied away from taking credit for his own work, preferring to focus on the contributions of others. When I (Peter) worked with him as the editor of his musical autobiography, Where Have All the Flowers Gone, it was frequently challenging to get him to even claim authorship of his own songs, as when he found a melody that worked perfectly with the lyrics that someone else had put together in the song "Step by Step". Countless people have told us how deeply they were affected by Pete's ideas and vision from attending his concerts years earlier. Countless others have told me the ways he supported them and helped them develop their musical gifts.

In August 2013, Pete called us up to tell us he had given away all his copies of Rise Up Singing and asked if we could sell him another 30 copies. When we drove by his house to drop off the books, he said cheerfully: "I am hoping to live to be 100. Then I'll get together a big party with all my friends and family. And then 'check out'." It was not to be. Seeger died of natural causes on Jan. 27, 2014. The thousands of people who cherished will continue celebrating his incredible life as long as they live.